Canada will be home to a new venture capital fund that will invest in enterprise cloud startups. Its backer? Salesforce Ventures, the global investment arm of Salesforce, a leading cloud-hosted business software provider.

According to a recent press release from Salesforce, the $100 million Canada Trailblazer Fund has already taken stakes in four Canadian startups building cloud-based tools for the enterprise, including Tier1CRM, Traction Guest, Tulip and OSF Commerce.

(Disclosure: Salesforce’s venture arm is an investor in Crunchbase News’s parent, Crunchbase. As with all investors in Crunchbase, Salesforce Ventures has zero input in the operation or coverage of the News team.)

The companies mentioned above join a handful of other Canadian enterprise cloud companies in Salesforce’s broader investment portfolio. In the years prior to announcing the new Canada Trailblazer Fund, Salesforce Ventures made investments in Aislelabs, Vidyard and LeadSift. And Salesforce itself participated in Fredericton, New Brunswick-based Introhive’s $7.3 million Series B round back in 2015.

Almost exactly one year ago, Crunchbase News profiled Salesforce Ventures and a new AI-focused fund it announced at the time. But instead of revisiting the firm and its investments, this time we’re going to take a look at the state of the market it’s jumping into.

Investors’ growing appetite for Canada’s cloud companies

Specifically, using Crunchbase data, we’re going to take a quick peek at Canadian companies in the “enterprise cloud” sector. To do so, we’ve pulled together a list of more than 1,000 companies in a wide variety of categories in Crunchbase. We used the enterprise applications, enterprise software, SaaS, CRM, sales automation, ERP, billing, meeting software, marketing animation, contact management and scheduling categories as a rough proxy for the kinds of markets on which Salesforce’s new fund may be interested.

And what did we find?

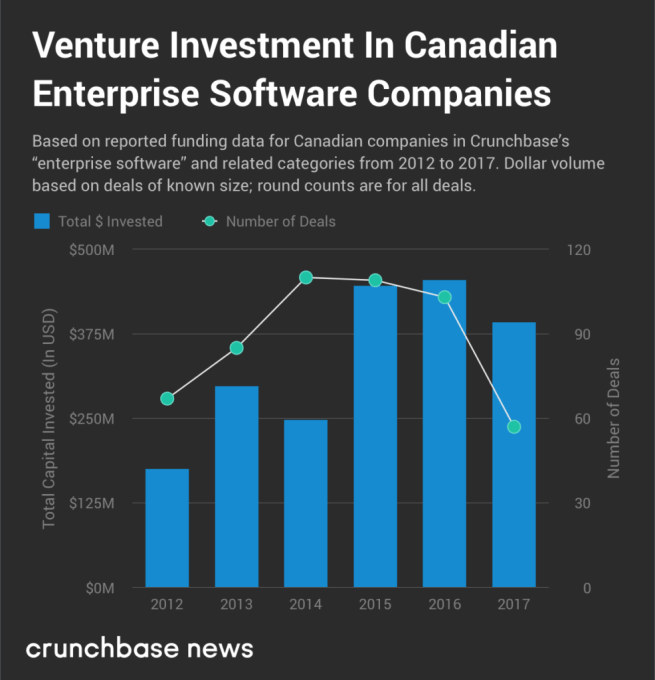

For one, there’s been a general uptick in venture investment activity in Canadian cloud companies, but that growth has come in fits and starts. Below, you’ll find a chart displaying aggregated annual venture investment data for Canadian cloud companies.

The above chart is based on reported data in Crunchbase, which, especially for seed and early-stage rounds, carries some reporting delays. These may not affect dollar volume figures (fledgling companies don’t raise all that much money), but reported deal volumes will undershoot reality for up to two years.

Regardless, between 2012 and 2017, reported venture dollar volume grew by approximately 124 percent.

2018: Off to a strong start on the investment side

Although it’s not pictured in the chart, so far in 2018 there have been more than 20 reported venture funding rounds in Canada for cloud companies in the categories we searched above. Here are some of the highlights so far:

- RFP management provider Loopio closed a CA$11 million Series A round led by OpenView, which Crunchbase News covered as it happened.

- Igloo Software, maker of a web-based suite of collaboration and productivity tools, closed $47 million in a Series C round led by Frontier Capital.

- Bench, a Vancouver-based bookkeeping service provider, raised $23 million in its Series B round, which was led by iNovia Capital.

- Uberflip, which develops and provides a content personalization service platform, raised $7.4 million in a Series A round led by Updata Partners.

- PointClickCare, a web-based SaaS platform for long-term care providers, raised CA$186 million in a late-stage venture round led by Dragoneer Investment Group.

With help of the PointClickCare round, Canada’s enterprise-focused cloud service startups may be on track to raise more capital in 2018 than they did in the prior year.

Where do Canada’s cloud companies reside?

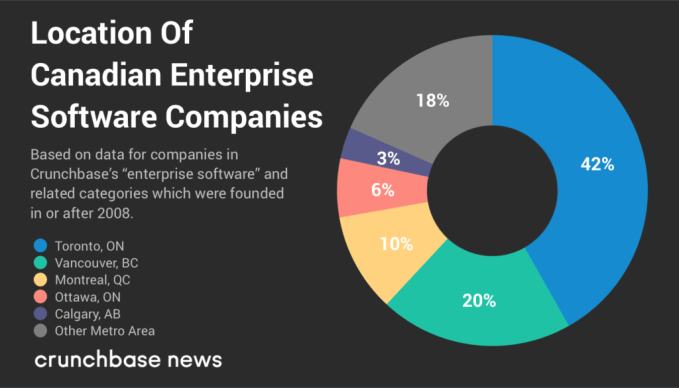

As for where the hot spots are for Canadian cloud companies, you shouldn’t be surprised that they’re based in the country’s major population centers. Below is a chart showing the distribution of headquarters for our list of cloud companies founded in the past decade.

This being said, it may make sense for Salesforce and other investors interested in Canadian cloud companies to start looking outside these major metro areas. The proportion of cloud companies founded elsewhere in Canada is on the rise. In our data set, around one-fifth of the cloud companies founded in 2008 were located outside the five major metro areas cited above. For companies founded in 2015 and 2017, half are headquartered in other Canadian metro areas.

It goes without saying that there are seemingly endless market niches in the enterprise cloud services market, and as such we just barely scratched the surface here. There are countless data points and anecdotes we didn’t cover here, like this fun fact: Slack, the seemingly ubiquitous workplace chat platform, was originally founded in Vancouver. (It’s since relocated HQ to San Francisco.) Another: Shopify, which is based in Ottawa, went public in May 2015 and raised nearly $131 million in the offering, making it one of Canada’s biggest-ever tech IPOs.

In its statement, Salesforce cited IDC research findings, which say that Canada’s public cloud software market will grow six times faster than on-premise deployments, reaching CA$4.1 billion by 2019. No doubt, there will be stiff competition among investors for an increasing number of Canadian companies seeking capital in years to come.

Source: Tech Crunch

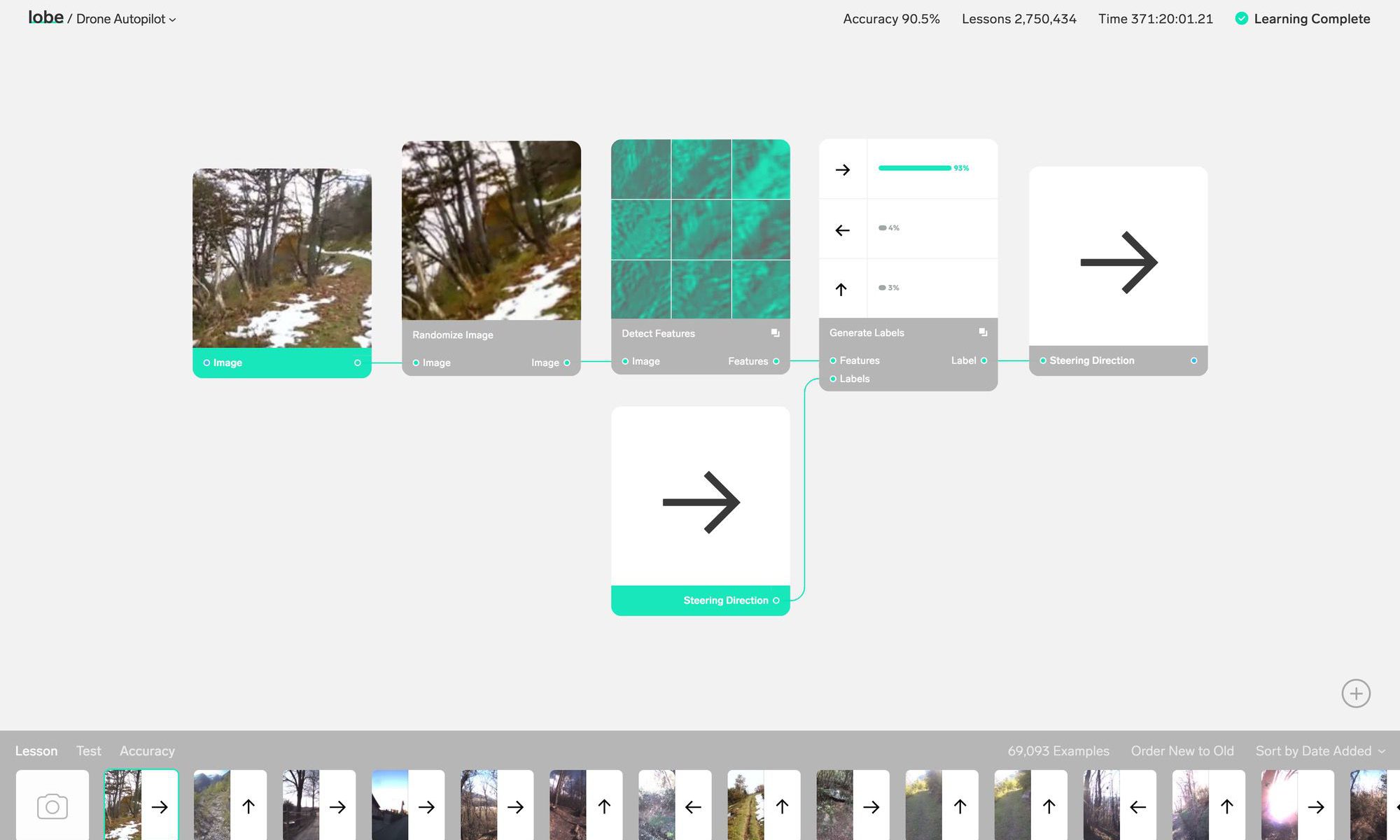

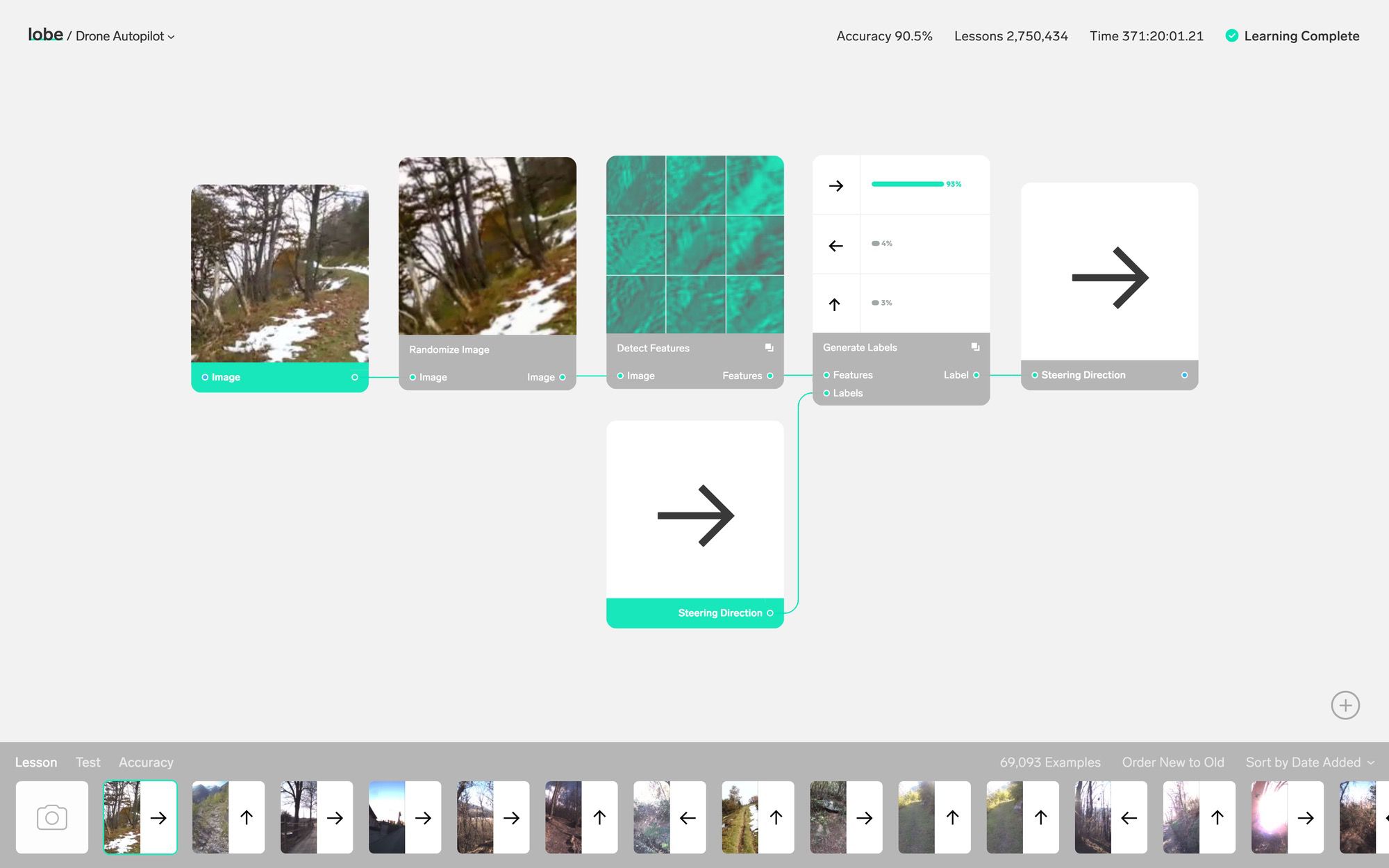

A raft of examples on the site show how a few simple modules can give rise to all kinds of interesting applications: reading lips, tracking positions, understanding gestures, generating realistic flower petals. Why not? You need data to feed the system, of course, but doing something novel with it is no longer the hard part.

A raft of examples on the site show how a few simple modules can give rise to all kinds of interesting applications: reading lips, tracking positions, understanding gestures, generating realistic flower petals. Why not? You need data to feed the system, of course, but doing something novel with it is no longer the hard part.

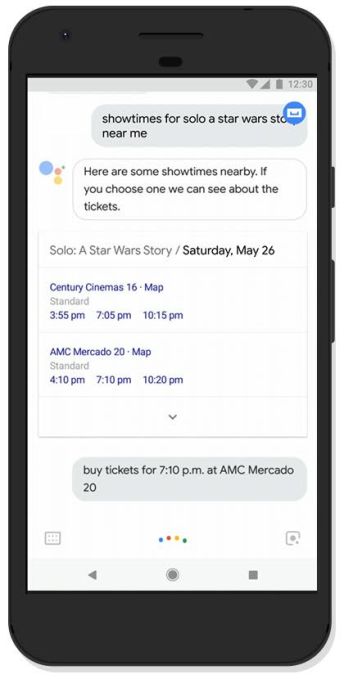

in honor of the Star Wars

in honor of the Star Wars