Matthew Carpenter-Arévalo

Contributor

Matthew Carpenter-Arévalo is a former Google and Twitter Manager and current CEO of

Céntrico Digital, a Latin American based digital agency.

One month ago, Yonathan Segovia, a Cabify driver originally from Venezuela, was allegedly attacked by a mob of taxi drivers on the streets of Quito in Ecuador.

In the video that documents the aftermath of his alleged assault, a short-of-breath Segovia narrates to his cell phone what happened. Behind him stand a few traffic police and a contingent of semi-formally dressed taxi drivers donning sunglasses and gesticulating to the police. Segovia directs the camera to the broken windshield and claims that he and his vehicle were attacked by xenophobic taxi drivers yelling fuera Cabify (get out Cabify) and regresa a tu país venezolanos (go back to your country, Venezuelans).

Though incidents of violence against drivers of ride-sharing apps are rare in Ecuador, the official taxi syndicate’s rhetoric has intensified as yellow cabs have become increasingly frustrated by what they perceive as government inaction over the encroachment of Uber and Cabify.

In neighbouring countries such as Colombia and Costa Rica, taxi drivers have attacked ride-sharing app drivers, their cars, and even passengers.

It had only been a few months after Segovia fled Venezuela’s violent streets that one of his brothers was murdered… killed in a case of mistaken identity, according to the young driver. He had come to Quito to escape, and instead found himself in the middle of a pitched battle between local taxi unions and an international ride-sharing company… a battle that had claimed foreign-born Cabify drivers as collateral damage.

Before choosing Ecuador as his new home, Segovia considered a number of countries in the region. To help make his decision he browsed Venezuelan expat groups on Facebook where people exchange information about their experience and ask for help. He considered going to Panama, but was dissuaded by reports of xenophobia against Venezuelans there.

He had about two months of salary saved for the journey and wanted to spend as little as possible on travel. He finally decided on Ecuador primarily because of its proximity and because the country has used the US dollar as its official currency since a financial meltdown in 1999. Having long abandoned his studies to be a civil engineer, Segovia now needed to send money home to help support his family. Earning US dollars represented the safest way to ensure the well-being of his dependents back home.

Segovia took the 2500 kilometer trip overland from Maracay on the Atlantic Coast to Quito. After arriving in the Ecuadorian capital he initially struggled to find work until he was taken on at a car-wash. Claiming to have suffered exploitation and abuse by the owner of the car wash because of his foreign status, Segovia left the car wash and was told by a friend about Cabify and so he signed up for the driver training.

Cabify enabled him to work flexible hours without suffering the type of discrimination he faced at the car wash. “It’s like I’m my own boss,” he says, although a boss that drives himself pretty hard. Most days Yonathan works 16-18 hour days. Thanks to his sacrifice, Yonathan has been able to send money back home to help his family leave Venezuela. No se vive en Venezuela, se sobrevive, (“No-one lives in Venezuela, they only survive.”) Segovia said. Now he has three brothers living in Argentina. All three drive for Uber.

Thousands of taxi drivers, shouting slogans against Uber such as Uber out and Down with piracy brought traffic to a near standstill in Bogota, the capital of Colombia, a city of more than 8 million people, on May 10, 2017. (Photo by Juan Torres/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Venezuelans are leaving their country in droves, and their plight is propelling the growth of ride-sharing apps across Latin America. Desperate for work, Venezuelans are flocking to neighbouring countries and often finding immediate employment as drivers for US-based Uber and its regional competitor, the Spanish-based Cabify.

Although the relationship between Uber, Cabify, and the Venezuelan diaspora is often mutually beneficial, it also could be easily perceived as exploitative. On the one hand, ride-sharing apps are the saving grace for many desperate migrants, providing a much needed sources of income. On the other hand, the precarious circumstances in which Venezuelans find themselves abroad means that they are incapable of negotiating the conditions of their employment, making them even more vulnerable to the one-sided conditions ride-sharing apps often impose on their drivers.

And the explosion of Venezuelan drivers has added a jingoistic element to the legal and regulatory battles between ride-sharing apps and taxi syndicates, pitting locally-born taxi drivers against foreign-born riding-sharing drivers in confrontations that sometimes become violent.

Venezuela was once a beacon for development in Latin America, which makes its current predicament all the more perplexing. In the 1960s Venezuela shed its military dictatorship and looked forward to becoming a developed country thanks to the discovery of the world’s largest oil reserves beneath Lake Maracaibo. Despite its vast potential, the benefits of Venezuela’s growth did not trickle down to the country’s poorest citizens.

People walk by graffiti with an image of late President Hugo Chavez in Caracas on May 11, 2018. – Venezuelan citizens face a severe socio-economic crisis, with hyperinflation – estimated at 13,800% by the IMF for 2018 – and shortages of food, medicines and other basic products. (Luis ROBAYO / AFP/Getty Images)

In 1999 Lt. Colonel Hugo Chavez, a populist strongman and failed coup-leader, was elected on a mandate to bring socialism to Venezuela by appealing to class divisions. Benefiting from record-high $100/barrel oil prices, Chavez re-directed the country’s oil wealth to the poor through a vast array of well meaning but unsustainable government welfare schemes. 14 years into his mandate, Chavez died of cancer in 2013. Shortly thereafter the bottom fell out of the price of oil, plunging to $26/barrel by 2016.

Chavez’s chosen successor, the former bus driver and union leader Nicolas Maduro, was elected in a contested vote in 2014. As oil wealth dried up, Venezuelans became aware of how years of socialist policies, including expropriations, had damaged the country’s non-oil productive capacity, making them over-reliant on imports and increasingly short of foreign exchange.

Rather than attempt to mend for errors past, Maduro doubled-down on socialism and oppression by attacking the media, violently suppressing protests, throwing his opponents in jail, and creating a parallel congress after voters gave a majority to an opposition coalition in 2015. From there Venezuela’s nightmare has become increasingly farcical. Two of Maduro’s nephews have been convicted for drug trafficking by the United States. The country’s current vice-president was also accused by the United States of drug trafficking, prompting sanctions. Mismanagement has driven Venezuelan oil-production to an all-time low. Slowly, the country is running out of cash. Inequality, the cornerstone issue for the self-nominated Bolivarian socialists, is actually worse than ever.

It’s hard to overstate the scale of the humanitarian, economic, political and social crisis that causes Venezuelans to leave. Food shortages are rife. Medicines are scarce. Inflation is expected to rise to 13,000% in 2018. Venezuela’s elections, including those held this month, are shambolic. Tropical diseases such as malaria that were controlled or eliminated in the 1960s are roaring back. According to the World Economic Forum, Venezuela was the sixth most dangerous country on the planet in 2017.

Leaving Venezuela is increasingly difficult. Airlines such as United, Delta, and regional heavyweight Avianca have suspended flights to Venezuela due to accumulating debts with the foreign-currency-strapped government. Many try to escape to neighbouring caribbean nations by boat, often with dire consequences.

Though precise numbers are difficult to obtain, we know that roughly a million Venezuelans have left the country in the past two years. While some will migrate to the United States, the vast majority will flee overland to neighbouring countries. Colombia alone has registered at least half-a-million legal migrants, while Brazil receives 800 migrants a day.

Often arriving without money or shelter, Venezuelan migrants depend on the networks of friends and family already established in their destination countries to find work. Through Mercosur, a regional trade block that includes most of the countries in South America, Venezuelans are usually able to qualify for working visas, though many work illegally because the costs of getting a visa are prohibitive. Whereas highly-educated Venezuelans have more luck in finding gainful employment, many Venezuelans join the troves of native-born citizens in either the informal economy or under-employment.

Ride-sharing apps are well-suited to Latin America because most major cities already operate with an extensive network of informal taxis. Cars with hand-made signs that say “taxi” often circulate in dense areas seeking brave passengers while avoiding both formal taxis and the police. Users are attracted to ride-sharing apps because of the additional security and the attention to detail in the quality of service. Whereas traditional taxis are looked upon suspiciously, Uber and Cabify allow for both traceability, on-demand services, and predictable prices, providing a safe and dependable mode of transport where there often isn’t any.

Both Uber and Cabify have focused aggressively on Latin America where the stakes are high. Two cities in Brazil, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, represent Uber’s biggest markets in terms of rides. Aside from Spain and Portugal, Cabify focuses exclusively on its operations in 12 Latin American countries. Chinese competitor Didi recently purchased Brazilian competitor 99 and promptly launched its first foreign operation in Mexico.

According to Uber, the company has more than 36 million active users in the region and provides employment for more than a million drivers. Cabify, on the other hand, claims to have 13 million users and to have grown its installed-base by 500% between 2016 and 2017.

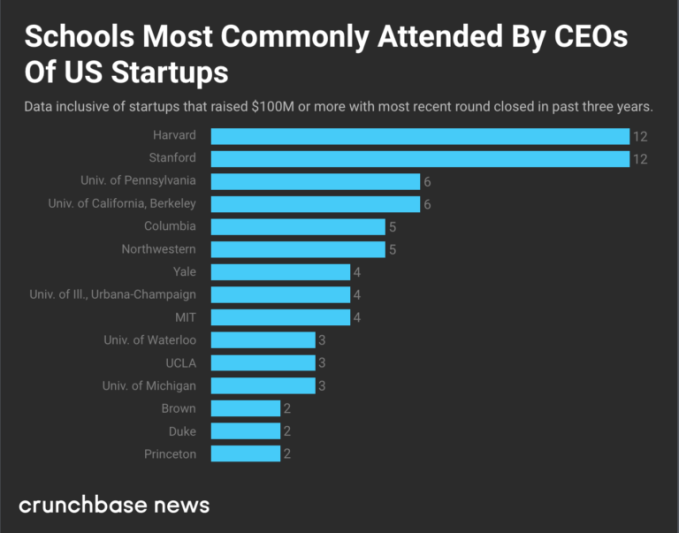

As reported in TechCrunch, Cabify’s parent-company Maxi Mobility recently raised $160 million at a $1.4 billion USD valuation. Maxi Mobility’s Series E comes just as Uber sold its east-asia operation to rival Grab, prompting CEO Dara Khosrowshah to disclose that the company is less focused on M&A and more focused on organic growth, thus encouraging the flush-with-cash Maxi Mobility’s Latin America push. Seeking scale, Maxi Mobility also acquired regional competitor EasyTaxi.

Though their business models are similar there are notable differences between how the two companies operate. Whereas Uber tends to invoice from abroad and thus avoid paying most local taxes, Cabify prefers to setup local entities and thus subject itself to local tax and regulatory regimes where possible. While Uber burns through cash, Cabify flirts with profitability.

The legal hurdles for ride-sharing apps in Latin America are similar to elsewhere in the world. Countries such as Mexico, Panama, and Uruguay have regulated ride-sharing apps. Others such as Argentina, have banned the apps’ operations. In most countries in Latin America, including large markets such as Brazil and Colombia, the apps find themselves in legal limbo as cases involving the companies make their way through the arduous and often politicized court systems.

Chilean taxi drivers demonstrate along Alameda Avenue against US on-demand ride service giant Uber, in Santiago, on July 10, 2017. / AFP PHOTO / Martin BERNETTI/Getty Images)

Though Uber was unable to disclose how many of its drivers in Latin America are Venezuelan expats, Cabify acknowledged that in Panama up to 60% of its drivers are Venezuelan nationals. In Ecuador and Argentina, the number is reported to be closer to 10%. The number of Venezuelan drivers in Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and Chile was not disclosed by either company. This presence of Venezuelan drivers across the continent has not only been noticed by tech-savvy business travelers with a keen ear for accents and a penchant for small talk. Panama went so far as to pass a law stating that ride-sharing app drivers must be Panamanian citizens.

Both companies acknowledge that they follow local legislation in hiring drivers. Neither company confirmed that they explicitly check immigration status prior to hiring a driver; however, they do require a local license which in turn requires a valid visa to obtain. Uber and Cabify require drivers submit an up-to-date police record from their country of residence, but not from the drivers’ previous countries of residence or countries of origin. Unless local legislation mandates limited hours, Uber and Cabify only sparingly limit the amount of time a driver can work, meaning drivers can work as much or as little as they like. Because of the informal nature of their work, drivers are not covered by national health insurance policies.

Because Venezuelans drivers are often new arrivals without credit history or savings, most negotiate agreements with vehicle owners who manage the relationship with the ride-sharing app. Vehicle owners like to keep their cars operating at close to maximum capacity in order to extract maximum value. Some will juggle as many as three drivers at a time in order to keep their vehicles in constant operation.

In markets where drivers are scarce it is common for drivers to negotiate 50/50 or 40/60 (40% for the driver, 60% for the owner) minus expenses including gasoline and insurance. While Cabify and Uber approve and train each driver and reserve the right to remove drivers from their fleet, the owners of the vehicles are responsible for paying the drivers. In an informal poll of drivers, most claimed to earn between $600 and $1000 USD per month, which is twice the minimum wage in many countries in Latin America and comparable to if not more than what taxi drivers make.

The same drivers claimed that they were making more with Uber and Cabify than they were working under the table in mostly service-sector jobs. Most drivers reported working more than 60 hours a week, well beyond the 40 hour work week legislated in most countries.

The Venezuelan drivers I spoke to across numerous countries generally speak well of Uber and Cabify whilst acknowledging their own vulnerable status. Many have stories to tell of vehicle owners that didn’t pay them, that docked their pay unnecessarily, or that were verbally abusive.

Drivers are dependent on vehicle owners to honor their verbal promises and they have no settlement mechanism to mediate disputes either through local governments or through the companies. For drivers who fall out with vehicle owners, their only option is to switch cars. After all, a driver with positive reviews and a clean record is attractive to vehicle owners hoping to maximize their return. None of the drivers I spoke to felt they were in a position to negotiate their working conditions with the ride-sharing apps.

While it’s not clear that Uber and Cabify are targeting Venezuelans fleeing the humanitarian crisis that has engulfed their homeland as part of their hiring strategy, it is clear that the companies have benefited immensely from their presence across Latin America, especially in smaller markets such as Panama, Ecuador, and Bolivia. Finding a pool of unemployed, eager and qualified drivers has allowed the companies to scale the supply-side of their business and thus ensure quick pick-up times for passengers, an essential feature for apps to become “sticky”.

As one vehicle owner stated, “Cabify entered the market right at the same time that Venezuelans were coming in higher numbers. The company never would have achieved critical mass [on the supply side] were it not for Venezuelans.” Uber and Cabify also benefit from the drivers’ powerlessness: because the alternative to driving for a ride-sharing app is often worse pay without protections, Venezuelan drivers accept the conditions dictated by the companies without protest.

Most of the countries in Latin America that are receiving Venezuelan migrants lack the infrastructure and the know-how to manage a massive influx of newcomers. Because many Latin American economies have large informal sectors, migrants quickly slip into the informal economy where they have neither benefits nor protections such as minimum wage. Uber, Cabify, EasyTaxi, Didi, etc., represent technologies that Latin American consumers have taken to because they offer a superior customer experience when compared to traditional taxi services.

Nonetheless, the status of these companies continues to be tenuous in countries such as Brazil and Colombia, where court cases drag-on slower than rush hour traffic in Sao Paulo or Bogotá. At the same time, politicians are reluctant to create legislation that will legalize ride-sharing apps for fear of upsetting powerful taxi unions. Ride-sharing apps offer a clear solution to an endemic transportation problem found in almost any Latin American city.

In many ways the problem these apps solve is caused by slow-to-change politicians and resistant-to-change taxi unions. Unfortunately, until local governments catch-up in providing legislation that protects drivers & fairly regulates ride-sharing apps., the growth of companies like Uber and Cabify in Latin America will be based partly on innovation, and partly on desperation and will always take place on the border of legality. In the meantime, as Latin American consumers jump into borrowed cars it’s worth remembering an adopted adage: there is no such thing as a free ride.

Source: Tech Crunch

There’s sunlight 24/7 for solar cells, water sequestered beneath the surface, and plenty of lovely regolith to build with (just don’t breath in the dust). “It’s almost like somebody set this up for us,” he said.

There’s sunlight 24/7 for solar cells, water sequestered beneath the surface, and plenty of lovely regolith to build with (just don’t breath in the dust). “It’s almost like somebody set this up for us,” he said.