There’s no doubt that modern social networks have let us down. Filled with hate speech and abuse, moderation and anti-abuse tools were an afterthought they’re now trying to cram in. Meanwhile, personalization engines deliver us only what will keep us engaged, even if it’s not the truth. Today, a number of new social networks are trying to flip the old model on its head — whether that’s attempting to use audio for more personal connections, like Clubhouse, eliminate clout chasing, like Twelv, or, in the case of new social network Telepath, by designing a platform guided by rules that focus on enforcing kindness, countering abuse, and disabling the spread of fake news.

Many of these early efforts are already facing challenges.

Private social network Clubhouse has repeatedly demonstrated that allowing free-flowing communication in the form of audio conversations is an area that’s notoriously difficult to moderate. The app, though still unavailable to the broader public, courted controversy in September when it allowed anti-Semitic content to be discussed in one of its chat rooms. In the past, it had also allowed users to harass an NYT reporter openly.

Meanwhile, Twelv, a sort of Instagram alternative, ditches the “Like” button concept and all the other features now overloading Instagram, which had once been just a photo-sharing network. But, unfortunately, this also means there’s no easy way to find and follow interesting users or trends on Twelv — you have to push friends to join the app with you or know someone’s username to look them up, otherwise it shows you no content. The result is a social network without the “social.”

Telepath, meanwhile, is a more interesting development.

It’s pursuing an even loftier goal in social networking — creating a hate speech-free platform where fake news can’t be distributed.

No social network to date has been able to accomplish what Telegraph claims it will be able to do in terms of content moderation. Its ambitions are optimistic and, as the network remains in private beta, they’re also untested at scale.

Though positioned as a different kind of social network, Telepath isn’t actually focused on developing a new sharing format that could encourage participation — the way TikTok popularized the 15-second video clip, for example, or how Snapchat turned the world onto “Stories.”

Instead, Telepath, at first glance, looks very much like just another feed to scroll through. (And given the amount of linked Twitter content in Telepath posts, it’s almost serving as a backchannel for the rival platform.)

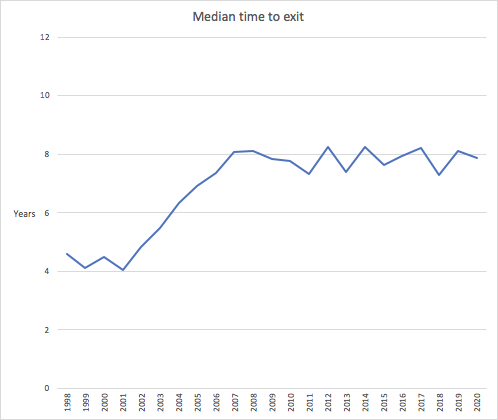

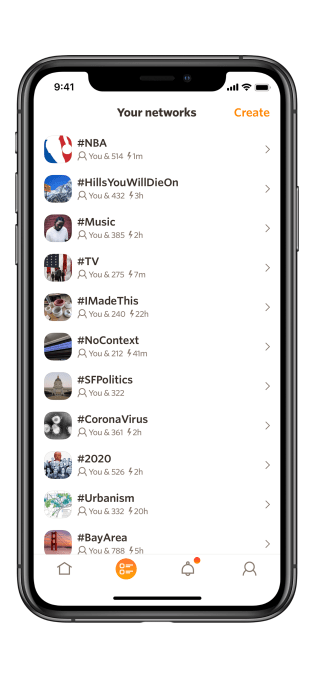

The startup itself was founded by former Quora employees, including former Quora Business & Community head, Marc Bodnick, now Telepath Executive Chairman; and former Quora Product Lead, Richard Henry, now Telepath CEO. They’re aided by former Quora Global Writer Relations Lead, Tatiana Estévez, now Telepath Head of Community and Safety; and Ro Applewhaite, previously research staff for Pete Buttigieg for America, now Telepath Head of Outreach.

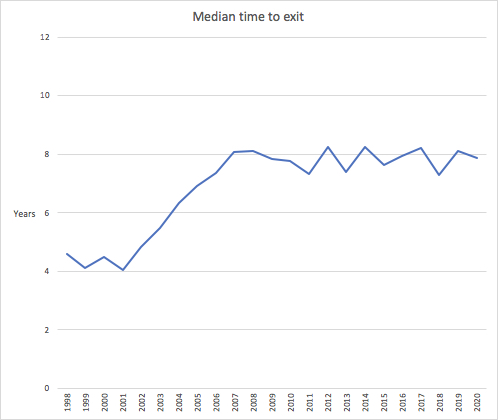

It’s backed by a couple million in seed funding, led by First Round Capital (Josh Kopelman). Other backers include Unusual Ventures (Andy Johns), Slow Ventures (Sam Lessin), and unnamed angels. Bodnick and his wife, Michelle Sandberg, also invested.

Image Credits: Telepath

When talking about Telepath, it’s clear the founders are nostalgic for the early days of the web — before all the people joined, that is. In smaller, online communities in years past, people connected and made internet friends who would become real-world friends. That’s a moment in time they hope to recapture.

“I’ve benefited a lot by meeting people through the internet, forming relationships and having conversations — that sort of thing,” says Henry. “But the internet just isn’t fun in the ways that it used to be fun.”

He suggests that the anonymity offered by networks like Reddit and Twitter make it more difficult for people to make real-world connections. Telepath, with its focus on conversations, aims to change that.

“If we facilitate a really fun, kind, and empathetic conversation environment, then lots of good things can happen. And it might be that you potentially find someone you want to work with, or you end up getting a job, or you meet new friends, or you end up meeting offline,” Henry says.

Getting Started

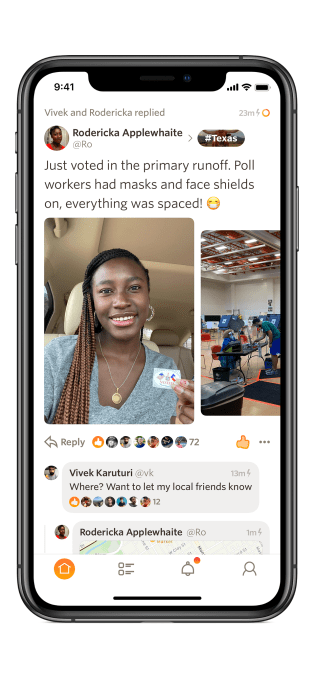

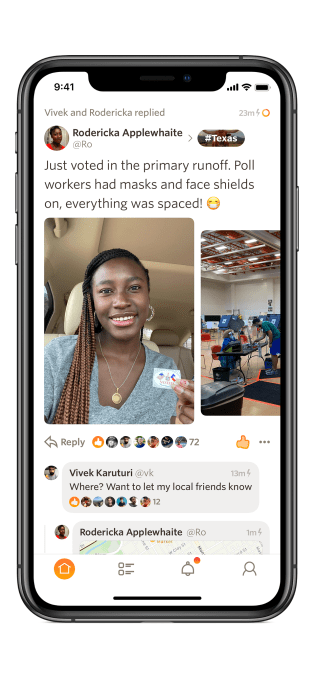

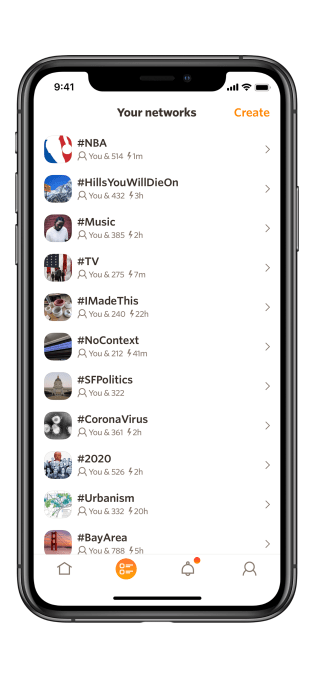

To get started on Telepath, you join the network with your mobile phone number and name, find and follow other users, similar to Twitter, then join interest-based communities as you would on Reddit. When you launch the app, you’re meant to browse a home feed where conversation topics from your communities and interesting replies are highlighted — orange for those replies from people you follow and gray for those that Telepath has determined are worth being elevated to the home screen.

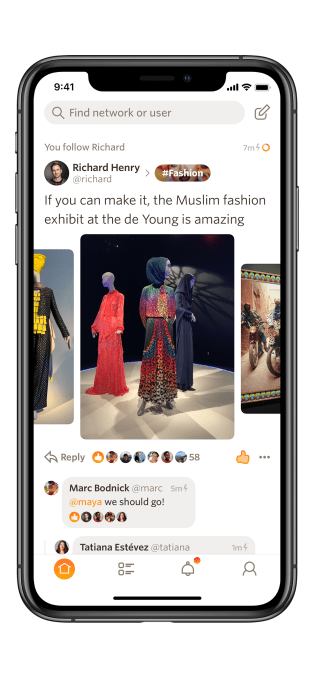

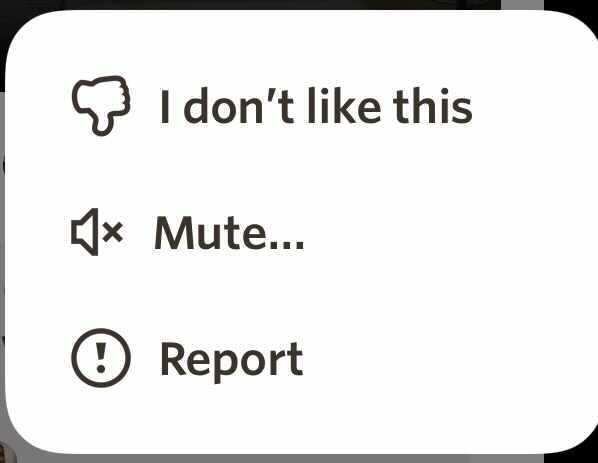

As you read through the posts and visit the communities, you can “Thumbs Up” content you like, downvote what you don’t, reply, mute, block, and use @usernames to flag someone.

Image Credits: Telepath, screenshot via TechCrunch

Another interesting design choice: everything on Telepath disappears after 30 days. No one will get to dig through your misinformed posts from a decade ago to shame you in the present, it seems.

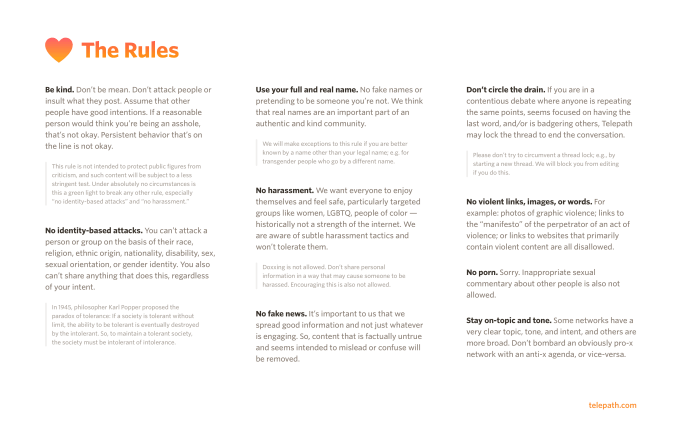

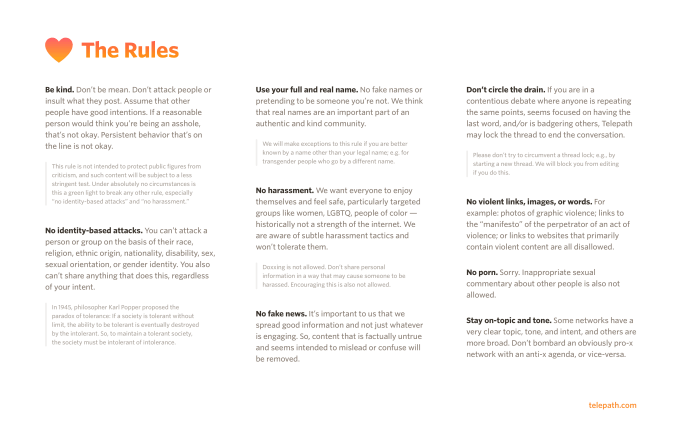

What’s most different about Telepath, however, is not the design or format. It’s what’s taking place behind the scenes, as detailed by Telepath’s rules.

Users who join Telepath must agree to “be kind,” which is rule number one. They must also not attack one another based on identity or harass others. They must use a real name (or their preferred name, if transgender), and not post violent content or porn. “Fake news” is banned, as determined by a publisher’s attempts at disseminating misinformation on a regular basis.

Telepath has even tried to formalize rules around how polite conversations should function online with rules like “don’t circle the drain” — meaning don’t keep trying to have the last word in a contentious debate or circumvent a locked thread; and “stay on topic,” which means don’t bombard a pro-x network with an anti-x agenda (and vice versa.)

Image Credits: Telepath

To enforce its rules, Telepath begins by requiring users to sign up with a mobile phone number, which is verified as a “real” number associated with a SIM card, and not a virtual one — like the kind you could grab through a “burner” app.

In order to the create its “kind environment,” Telepath says it will sacrifice growth and hire moderators who work in-house as long-term, trusted employees.

“All the major social networks essentially grew in an unbounded way,” explains Henry. “They had 100 million-plus active users, then were like, ‘okay, now how do we moderate this enormous thing?’,” he continues. “We’re in a lucky position because we get to moderate from day one. We get to set the norms.”

Moderation

“Day one” was a long time in the making, however. The team rebuilt the product four times over a couple of years. Now, they say they’ve developed internal tools that provide moderators with visibility into the system.

According to moderator head Estévez, these include a reporting system, real-time content streams organized in to buckets (e.g. a bucket for “only new users”), as well as various searchable ways to get context around a report or a particular problematic user.

“Really good tools — including real-time streams of content, classifiers for problematic behavior, searchable context, and making it hard for banned users to return — mean that each moderator we hire will be quite scalable. We think that there are network effects around positive behavior,” she says.

Image Credits: Telepath

“It’s our intention to scale up fast and high accuracy moderation decision-making, which means that we’re going to be investing a lot of engineering effort in getting these tools right,” she adds.

The founders have decided not to use any third-party systems to aid in moderation at this time, they told TechCrunch.

“We looked at a bunch of off-the-shelf [moderation systems], and we’re basically building everything that we need from scratch,” says Henry. “We just need more control over being able to tweak how these systems work in order to get the outcome that we want.”

The investment in human moderation over automation will also require additional capital to scale. And Telepath’s decision to not run ads means it will eventually need to consider alternative business models to sustain itself. The company, for now, is interested in subscriptions, but hasn’t made decisions on this front yet.

Banning the trolls

Though Telepath has only 4,000-plus users in its private beta, the two-person moderation team is already tasked with moderating posts from across the thousands of pieces of content shared on a daily basis. (The company doesn’t disclose how many violations it takes action against per day, on average.)

When a user breaks the rules, moderators may first warn them about the violation and may require them to take down or edit a specific post. No one is punished for making a mistake or being unaware of the rules — they’re first given a chance to fix it.

But if a user breaks the rules repeatedly or in a way that seems intentional, such as engaging in a harassment campaign around another user, they are banned entirely. Because of the phone number verification system, they also can’t easily return — unless they go out and purchase a new phone, that is.

These moderation actions don’t necessarily have to follow strict guidelines, like a “three strikes rule,” for example. Instead, the way the rules may be enforced are determined on a case-by-case basis. Where Telepath leans towards stricter enforcement is around intentional and flagrant violations, or those where there’s a pattern of bad behavior. (As with Reply Guys and sealioning behavior.)

In addition, unlike on Facebook and Twitter — platforms that sometimes seem to be caught off guard by viral trends in need of moderation — Telepath intends for nothing to go viral on its platform without having been seen by a human moderator, the company says.

Fake News

Telepath is also working to develop a reputation score for users and trust scores for publishers.

In the case of the former, the goal is help the company determine how likely the user is to break Telepath’s rules. This isn’t developed yet, but would be something used behind the scenes, not put on display for all to see.

For publishers, the trust score will be how factually correct they are what percentage of the time.

“For example, if the most popular article in terms of views from the publisher is just completely factually incorrect or intentionally misleading…that should have a bigger penalty on the trust score,” explains Henry. “The problem is that the incumbent platforms have rules against disinformation, but the problem is that they don’t enforce them out of this desire to appear balanced.”

Bodnick adds this challenge is not as insurmountable as it seems.

“Our view is that, actually, a handful of outlets are responsible for most of the disinformation…I don’t think our intent is to build out some modern-day truth system that will figure out if The Washington Post is slightly more accurate than The New York Times. I think the main goal will be to identify repeat disinformation publishers — determine that they are perpetual publishers of disinformation, and then crush their distribution,” says Bodnick.

This plan, however, involves setting rules on Telepath that fly in the face of what many today consider “free speech.” In fact, Telepath’s position is that free speech-favoring social networks are a failed system.

“The problem, in our view, is that when you take this free-speech centered approach that sort of says: ‘I don’t care how many disinformation posts Breitbart has published in the last — three years, three months, three weeks — we’re going to treat every new post as if it could be equally likely to be truthful as any other post in the system,’” says Bodnick. “That is inefficient.”

“That’s how we will scale this disinformation rule — by determining which relatively small group of publishers — I’m guessing it’s hundreds, low hundreds — are responsible for publishing lots of disinformation. And then take their distribution down,” he says.

This opinion on free speech is shared by the team.

“We’re trying to build a community, which means that we have to make certain tradeoffs,” adds Estévez. “In the rules we refer to Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance — to maintain a tolerant society, you have to be intolerant of intolerance. We have no interest in giving a platform to certain kinds of speech,” she notes.

This is the exact opposite approach that conservative social media sites are taking, like Parler and Gab. There, the companies believe in free speech to the point that they’ve left up content posted by an alleged Russian disinformation campaign, saying that no one filed a report about the threat, and law enforcement hadn’t reached out. These MAGA-friendly social networks are also filled with conspiracies, un-fact checked reports, and, frankly, a lot of vitriol.

The expectation is that if you go on their platforms, you’re in charge of muting and blocking trolls or the content you don’t like. But by their nature, those who join these platforms will generally find themselves among like-minded users.

Twitter, meanwhile, tries to straddle the middle ground. And in doing so, has alienated a number of users who think it doesn’t go far enough in counteracting abuse. Users report harassment and threats, then wait for days for their report to be reviewed only to be told the tweet in question didn’t break Twitter’s terms.

Telepath sits on the other end of the spectrum, aggressively moderating content, blocking and banning users if needed, and punishing publications that don’t fact check or those that peddle misinformation.

“Kindness” carve-outs

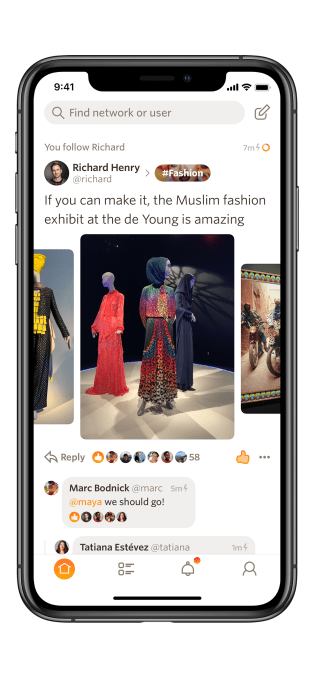

And yet, despite all this extra effort, Telepath doesn’t always feature only thoughtful and kind-hearted conversations.

That’s because it has carved out an exception in its kindness rule that allows users to criticize public figures, and because it doesn’t appear to be taking action on what could be problematic, if not violating, conversations.

Image Credits: Telepath

A user’s experience in these “gray” areas may vary by community.

Telepath’s communities today focus on hobbies and interests, and can range from the innocuous — like Books or Branding or Netflix or Cooking, for example — to the potentially fraught, like Race in America. In the latter, there have been discussions about the capitalization of “Black” where it was suggested that maybe this wasn’t a useful idea. In another, sympathy is expressed for a person who was falsely pretending to be a person of color.

In a post about affordable housing, someone openly wondered if a woman who said she didn’t want to live near poor people was actually racist. Another commenter then noted that gang members can bring down property values.

A QAnon community, meanwhile, discusses the movement and its ridiculous followers from afar — which is apparently permitted — though supporting it in earnest would not be.

There are also nearly 20 groups about things that “suck,” as in GOPSucks or CNNSucks or QuibiSucks.

Anti-Trump content, meanwhile, can be found on a network called “DumbHitler.”

Meanwhile, online publishers who routinely post discredited information are banned from Telepath, but YouTube is not. So if feel you need to share a link to a video of Rudy Giuliani accusing Biden of dementia, you can do so — so long as you don’t call it the truth.

And you can post opinions about some terrible people in which you describe them as terrible, thanks to the public figure carve-out.

Cheater and deadbeat dad? Go ahead and call them a “disgusting human being.” VP Pence was referred to by a commenter as “SmugFace mcWhitey” and Ronny Jackson is described as “such a piece of sh**.”

Explains Estévez, that’s because Telepath’s “be kind” rule is not intended to protect public figures from criticism.

“It is important to note that toxicity on the internet around politics isn’t because people are using bad words, but because people are using bad faith arguments. They are spreading misinformation. They are gaslighting marginalised groups about their experiences. These are the real issues we’re addressing,” she says.

She also notes that online “civility” is often used to silence people from marginalized groups.

“We don’t want Telepath’s focus on kindness to be turned against those who criticize powerful people,” she adds.

In practice, the way this plays out on Telepath today is that it’s become a private, closed door network where users can bash Trump, his supporters and right-wing politicians in peace from Twitter trolls. And it’s a place where a majority agrees with those opinions, too.

It has, then, seemingly built the Twitter that many on the left have wanted, the way that conservative social media, like Gab and Parler, built what the right had wanted. But in the end, it’s not clear if this is the solution for the problems of modern social media or merely an escape. It also remains to be seen whether a mainstream user base will follow.

Telepath remains in a closed beta of indefinite length. You need an invite to join.

Source: Tech Crunch