You’d think everybody would want to fly. It’s been a universal human dream since the first cave person saw the first pterodactyl¹. You’d think better technology, greater demand, economic growth, and population growth would mean more and more pilots. But the surprising, counterintuitive fact is that fewer and fewer people are flying, and now Earth needs pilots, badly.

“Airline industry facing a massive shortfall of pilots.” “Yes, there is a definite pilot shortage. It is true in all parts of aviation.” “The US Air Force is short more than one-quarter of the fighter pilots it needs.” “Asian airlines are running out of trained pilots.” “‘Extraordinary’ Pilot Shortage Threatens Flights; 637,000 Needed.”

Meanwhile, the number of active pilots in the US has declined from over 800,000 in 1980 to barely 600,000 in 2017, a quarter of whom are student pilots, a certificate for which you need no experience at all. Of course there are pilots and there are pilots. A private pilot in a little Cessna is very different from an airline transport pilot guiding a 777. And one reason there’s a shortage is that, while that 777 pilot pulls in six figures, an overworked copilot at a remote feeder airline gets paid peanuts.

But this overall broad decline in piloting is still truly remarkable. Why are we flying so much less in person, at the same time that we are flying so much more remotely? (The demand for commercial drone pilots, who in the USA must qualify for a “remote pilot certificate” by passing an aeronautical knowledge exam and a TSA security check, is also growing.) Why are fewer and fewer people taking to the skies, when they have never been more accessible, and flying car startups, some of them self-flying, are erupting like mushrooms after rain? Might self-flying airplanes ultimately solve the pilot shortage?

To try to answer these questions and more, I have recently taken up flying lessons myself, as a sterling example of investigative journalism on behalf of TechCrunch’s readers.

I jest. Really this was my friend Nat’s fault. “The thing about flying,” he said to me over dinner once, “is it combines romance, adventure, science, and exploration.” A heartbeat of stunned silence later I managed to retort, “Well, that sounds terrible,” but the damage was done.

Taking off seems easy enough, at first, on a demo flight. Just thrust the throttle forward, and feel the whole airplane thrill with the engine’s unleashed power as you accelerate down the enormous runway. The flight instructor next to you tells you when to pull up, gently — you’re not even moving that fast, maybe 70 miles an hour, normal highway speed — but when you do, just like that, you’re flying. You are so accustomed to vehicles on wheels that the freedom from the tyranny of the earth, the absence of the sensation of ground against tires, feels almost vertiginous, like weightlessness.

Around you the earth falls away: runway, airport, golf course, the San Francisco Bay glittering in the sun. From a cockpit 2500 feet up the Bay Area looks almost too gorgeous to be real, like a special-effect matte painting of sea, rippling hills, great pale swathes of buildings, cargo ships arrayed in their unloading queue, the forest of skyscrapers that is downtown San Francisco, the pale arc of the Bay Bridge, the clenched fist of Alcatraz, the famed distant silhouette of the Golden Gate.

I’m a terrible cliché now, of course. A Bay Area tech CTO who takes up flying is about as remarkable as a coastal Australian who takes up surfing. I blame Nat.

Does self-deprecatingly admitting that you’re a terrible cliché make it better or worse?

“Science,” he said, and there’s some of that, but really it’s mostly engineering, a kind very different from the engineering I know professionally. This is physical, visceral, greasy. Not a Matryushka doll of nested software abstractions, running on some faraway server whose physical details you don’t know or care about; not digital chipsets and circuit boards, taking advantage of Moore’s Law and the peace dividend of the smartphone wars, to drive LEDs or solenoids or little electric motors. This is airfoils, spars, composite materials, airflow vortices, a shifting center of gravity as fuel burns, physical forces fighting to keep you aloft against the relentless pull of the Earth. This is pistons, spark plugs, carburetors, magnetos, fuel pumps, propellers.

You need to understand how all this engineering works because it is there to keep you aloft and alive. Light aircraft are not dangerous — the one I’m learning in, the Diamond DA-40, a 21st-century airplane with an excellent safety record, is statistically safer per hour than a motorcycle — but that’s because of pilot training, not their inherent security. Whether you like it or not, part of the adventure of flying is that it’s replete with risks. Weather risks, largely: thunderstorms, icing, wind shear, and especially clouds.

(Yes, clouds. Basic pilot training is for “VFR” (visual flight rules) and if you’re not trained to fly “IFR” (instrument flight rules) then clouds can and will kill you, because without a visual horizon to track, your instincts and senses will promptly start telling you lies about your airplane’s attitude and behavior, and if you’re not trained to override those gut feelings, and follow what the instruments say, then you are asking for a controlled flight into terrain. Fun fact: night flights over water can still be “VFR” in the USA! See also the sad fate of JFK Jr.)

But technical risks are very real too. Did water get into your fuel tanks? Were they accidentally filled with jet fuel instead of avgas? How do you know? Is your engine running rough today? Maybe you just need to lean the mixture for a few minutes during the run-up; and maybe you need to turn around and call a mechanic. What speed will this airplane stall at? Trick question! Stalls aren’t dictated by speed. You better know what they are dictated by, if you want to fly.

And you do. Or at least I do. It’s glorious. It’s adrenalinizing, it’s breathtaking; it’s freedom, it’s beauty; it’s like dreaming while awake.

That said, learning to fly is frequently more Type II fun than Type I. I always actively enjoy it while I’m doing it, but at the same time, it is often tense, draining, and stressful. You need to always be on when you are in the cockpit. It takes time to get accustomed, at a gut level, to hurtling through the sky at high speeds in a little shell of fibreglass and carbon fibre with wings and a tail. And at least at first, you are drowning in information and obligations.

Student piloting is brief periods of pleasant inactivity interspersed with frequent periods of frantic multitasking. Aviate, Navigate, Communicate, they say — but at first aviation alone seems to take more attention and brainpower than you can allocate. You have rudders, ailerons, elevators, trim, and throttle to control. Sometimes you need to tweak the propellor, the mixture, and the active fuel tank. All this while constantly watching your airspeed, altitude, heading, and vertical speed; maintaining awareness of your engine indicators; and keeping an eye out for other airborne traffic.

It’s easier than that sounds, but it’s not as easy as it looks. Even takeoffs are harder than they first seem. (When you push the throttle forward, four separate physical forces skew the nose of the airplane sharply to the left, so you need to step on the rudder, without stepping on the brake, to keep the nose straight-ish.) Landings are hard full stop. Well, sometimes they feel easy, but consistency is hard.

Are self-flying planes on the horizon? I am skeptical, barring a new breakthrough in machine learning, which admittedly I don’t rule out. But there are two barriers. First, when will safe self-flying be possible? Self-driving cars are hard enough, and they only have one axis of control, and don’t get blown around by winds, and if something goes wrong you hit the brakes. Airplanes have pitch and roll as well as yaw, and move within a highly dynamic medium, and if something goes wrong — like an engine failure, or a bird strike — a quick halt is generally the exact opposite of a desirable outcome. I can easily envision self-flying AI which handles 99.99% of flights, but that 0.01% of exceptional situations will be awfully hard to train for.

Second, even if we get there, when will it be practical? While individuals might volunteer to be bleeding-edge adopters, how can you prove its validity to the FAA and other regulatory authorities? We’d need to add many more nines before self-flying software start competing with professional human pilots, who, unlike human drivers, have a remarkable safety record; commercial aviation had zero fatalities in 2017. Better autopilots for ordinary conditions are one thing, but removing pilots from flying entirely is quite another. Maybe after we build up a long, deep history of perfect safety with comparable drones or military flights; but not any time soon.

Better technology will however help with navigation. I don’t mean point-to-point, I mean in familiar places. Navigation may seem relatively easy above the San Francisco Bay, a well-known territory full of landmarks. Guess again. That sky may be empty but it is not unoccupied. Instead it is segmented into dozens of complex three-dimensional zones, and woe betide you if you stray into the wrong one.

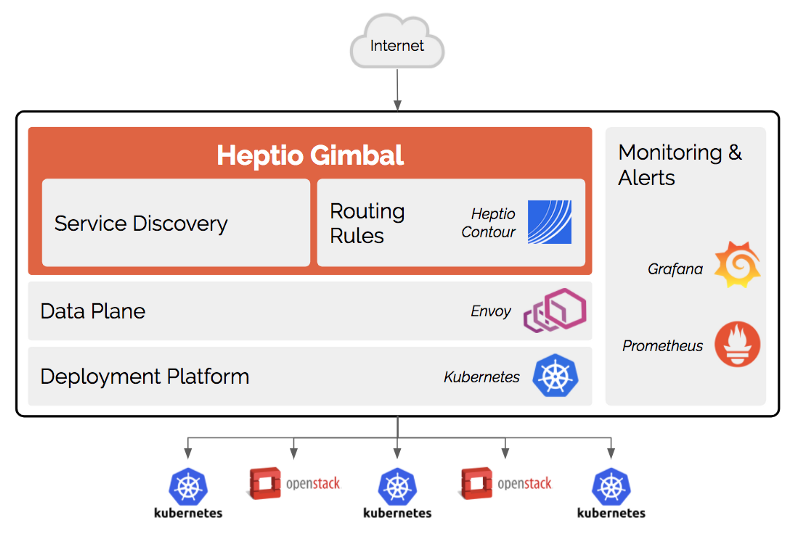

Bay Area VFR airspaces

Picture a tiered wedding cake, upside-down, with radiuses measured in miles. That’s the airspace of San Francisco International. But right across the bay you have Oakland International, which has its own smaller but still sizable wedding cake, and a little south San Jose International has its own, and both of those intersect with SFO’s. Then you have the half-dozen smaller regional airports, each jealously guarding their own disc of space, except where squashed by one of those cakes. Each of those kinds of airspace has its own rules and regulations. (SFO’s have the virtue of being exceedingly simple, for student pilots: keep out.)

You may not enter any of those airspaces without first communicating with their controllers, and to communicate you first must master aviation’s clipped, dense, custom language. “Hayward Tower, Seven Papa Victor holding short at runway Two Eight Left Alpha, request right crosswind departure.” “Norcal Approach, DA-40 Seven Eight Seven Papa Victor, three thousand over Lake Chabot, inbound to Oakland for touch-and-gos with information Foxtrot.” “Seven Papa Victor, squawk oh three five seven and contact Oakland Tower.” It would be unremarkable to change frequencies several times, and talk to a few different controllers, during a half-hour Bay flight.

Knowing what frequency to use, what to say, who to say it to, and when, while picking your own call sign out of the frequent chatter, most of which is irrelevant to you, and parsing / copying down the important information you need — that would be nontrivial all by itself, at first. But it’s not by itself. It’s something you do simultaneously with everything else you’re doing while flying the airplane.

Does the heavy use of voice communications over frequently (and manually) shifted shared channels seem a little … well … twentieth century? A little technologically backward? Well, yes, and no. Voice over radio is simple, powerful, flexible, and time-tested. There are a lot of old airplanes and old pilots out there. Aviation as an industry is understandably loath to make rapid changes — many of its rules are, as they say, written in the blood of people who learned the need for them the hard way.

That said, modern aircraft like the DA-40s I’m learning on tend to have “glass cockpits,” with one LED screen displaying an artificial horizon and all the important instrument data so you don’t have to look at the actual dials (which are still there as backup), and the other displaying a zoomable map with terrain, your heading, airspace boundaries, nearby traffic, etc., and containing databases of information such as airport locations, runways, and frequencies — all at your fingertips if you can master their baffling and perverse knob-and-button user interfaces. (“Turn the big knob left. Now turn the little knob right. Now push ENT. Now turn the little knob left…”)

Apps like ForeFlight make it easier yet. And we happen to be 20 months away from a massive technological phase shift in general aviation, after which much American airspace will require “ADS-B” technology that will essentially let every aircraft be tracked in 3-D in real time; this should make communications and aircraft spacing much easier.

It feels a little bureaucratic, it’s true. The romance of the glory days of flight, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and company wrestling their planes over the Andes and the Sahara, with the freedom of the whole sky thanks to their skill and their machinery, feels distant from today’s strictly ruled, tightly regimented airspaces, and constant surveillance anywhere near a major airport. But then the skies were empty back then, and the machinery all too often so lethal that skill meant nothing, in the end.

And, I mean, these too are the glory days. You can fly. All by yourself. It isn’t an easy thing to learn, or to do. (OK, some people are naturals. I myself am not.) Multitasking is hard. Kinesthetic learning is hard. Establishing new muscle memories is hard. Developing good judgement is hard. Flying an airplane smoothly, with coordinated turns (using the ailerons and rudder together) while maintaining precise control of altitude and airspeed and bank angle, is … actually that’s not so difficult; but doing all this while at the controls of an aircraft that’s, say, being buffeted by crosswind gusts as you turn towards a runway, in a busy traffic pattern, with the stall warning beginning to whine because you banked too late and too hard, but it’s too late to fix that judgement error now, and the radio crackling in your ears as the tower says something which might or might not be germane to you —

— well, the instructor who made that first takeoff seem easy told me, later that same day, that most people who begin pilot training never finish it. There are plenty of good reasons for that. It is, as my friend Dillo put it, more expensive than a crack habit. People hit plateaus and get frustrated and give up. But I think the main reason is because it’s complicated, and difficult, and stressful, and when the lessons stop being novel, people stop forcing themselves to do the hard thing, despite the ultimate rewards.

Is that why there are far fewer pilots in America than there were in 1980, even though there are 100 million more people? Would better, modernized navigation and communications technology go a long way towards making flying a little less draining, and a little more appealing? Maybe. There are cultural reasons, too, though, and I think they’re more significant. I think we now lean more towards the abstract than the physical, and towards comfort rather than adventure.

I remember, years ago, seeing online reactions to a study reporting that teenagers in gifted programs were likely to quickly drop things they weren’t immediately good at, the theory being that they feared losing their gifted designation, and that this instinct persisted into adulthood. An astonishing number of my friends, especially my friends who worked in tech, said they strongly identified with this. I wonder if that’s a factor.

Most of all, though, I think flying seems like a very 20th-century activity in the popular imagination. But I suspect that won’t last. Something, whether hardware or software, will catapult it into the 21st century mindset soon enough.

¹Yes, I know. It’s a joke.

Source: Tech Crunch